Last week I attended the “Postcolonial Education” symposium, co-organized by Leeds Beckett University, the University of Leeds and the Northern Postcolonial Network. The day brought together early career researchers, poets, community educators and established academics to think critically about teaching, learning and schooling. It was exactly what I needed as the end of term nears: a space for recuperation, renewal and strengthening.

The event began with some powerful readings from the poet Malika Booker. Her moving performance of “A List of Conservative Variables” was dedicated to Labour MP, Jo Cox, whose tragic murder the previous day was in everyone’s minds throughout; a horrifying reminder of the vulnerability of progressive activists everywhere.

Following Malika, there was a round-table discussion involving early career academics who—in very different but complementary ways—researched the presence of colonial ideas and norms in education, past and present. John Cocking explored the evolution of higher education in British Malaya, showing how elite engagement with an imperial curriculum ran in tandem with the neglect of the wider population. Helen Garnett showed how post-colonial Zambian elites have continued to seek British qualifications, in part because of the deliberate policies of the UK government as the colony moved to independence and continued diplomatic efforts thereafter. Danielle Hall talked about a project at Leeds Beckett that was exploring the utility of autobiographical texts for facilitating intercultural understanding in higher education, discussing its potential for decolonizing teaching practices. Frances Hemsley explored Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera’s experiences of education, interrogating his textual (and psychological) strategies for dealing with the ambivalence of its imperial nature. Kate Highman situated South African novelist Zoe Wicombe’s short story ‘A Clearing in the Bush’ within current student activism in the country, using the story to open a critique of how English literature is taught in historically-black institutions. And Shambhavi Priyam discussed the differing colonial and post-colonial fates of three indigenous languages in India (Khasi, Santhali and Gondi) as they acquired scripts, drawing out the hegemonic status of Hindi and English as academic languages.

The academic round-table discussion that followed did not focus on peoples’ research, but on their teaching. Literature scholars Claire Chambers, Kate Houlden, Sarah Lawson Welsh and Emily Zobel Marshall generously per-circulated some of their syllabi to start the conversation. The boundary between diversifying the curriculum and decolonizing it was a really productive point of discussion, along with strategic questions over maintaining specialized modules on postcolonialism against embedding the subject within several core modules spread across a degree programme. The participants spoke candidly about their teaching experiences. Kate Houlden discussed the differing racial composition of courses she had taught in different institutions, and noted the contrasting seminar dynamics that resulted. She also addressed her own whiteness in the classroom and as a representative of the academic community. For me, the opportunity to share teaching experiences and practices, and to openly reflect on our own embodied and subjective presences in the classroom, was really productive. Too often the body of the academic in the seminar is under-examined.

Khadijah Ibrahim then spoke about the inspirational Leeds Young Authors, a local community project that helps young people from a diverse range of backgrounds into the performing arts. Khadijah explained the history of the organisation and what it did. We were treated to a viewing of one of their shows and a powerful performance of a poem, read by two current students.

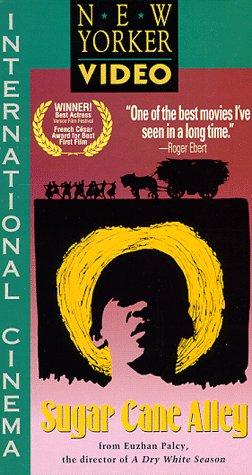

At the end of the day we watched the 1983 film adaptation of Martiniquan author Joseph Zobel’s novel Rue Cases Nègres (Black Shack Alley, changed to Sugar Cane Alley for US audiences), directed by Euzhan Palcy—a pioneering black, female French director. Joseph Zobel’s daughter, Jenny Zobel, and granddaughter, Emily Zobel Marshall, shared insights into Joseph’s incredible life and works. Although it was new to me, it is classic film, much cherished by Caribbean communities. The affecting story of young José’s formal education in colonial Martinique, supported by the relentless and selfless labour of his grandmother working in the sugar fields, profoundly captured a theme that ran through the day: the ambivalence of education being potentially liberating, whilst also being oppressive and marginalizing.

In the early career round-table, Kate Highman quoted Gayatri Spivak, saying that, “The task of a humanities teacher is to provide a non-coercive rearrangement of desire in the classroom.” This phrase struck home with me. The recent months have seen the “imagined community” of Britain invoked in alarmingly exclusive terms during a feverish and ugly EU referendum campaign. Non-British “Others” (particularly migrants and refugees from east of Germany and south of the Mediterranean) have been rendered into spectral threats to the nation, itself an ill-defined entity that both sides agree is “great” despite its historical fluidity and conceptual vagueness. In this context, the symposium has got me to appreciate anew the importance of postcolonialism in teaching and to value my part in rearranging desires that would frame Syrian asylum seekers as dangers rather than endangered.

**Military Coup**

Please consider supporting the people of Myanmar in their struggle for democracy by donating to one or more of the following organizations.

To support protestors and strikers:

- Mutual Aid Myanmar https://www.mutualaidmyanmar.org/

- Friends of Myanmar https://chuffed.org/project/support-the-myanmar-people-in-their-fight-for-freedom

- All Burma Federation of Trade Unions https://www.gofundme.com/f/abftu

- Myanmar Communities Against the Coup https://chuffed.org/project/myanmar-activists-emergency-funds

- Asia Pacific American Labour Alliance https://uk.gofundme.com/f/support-myanmar-workers-under-attack

To support internally displaced people:

- Phan Foundation https://phanfoundation.org/appeal-for-idps/

- Kawthoolei Today https://chuffed.org/project/support-myanmar-idps-seeking-refuge-from-military-junta

To support journalism:

- Myanmar Now https://www.myanmar-now.org/en/donate

- Operation Hanoi Hannah https://www.ophanoihannah.com/ (bottom of page)

I couldn’t make this so thank you for the blog .